As reported by Millie Knapp & James Ring Adams for American Indian Magazine in the Summer 2019 issue. Read the article online or pick up a copy of this issue on-site at Jacob’s Pillow, August 7-11.

Red Sky is Expanding the Views of the Indigenous World –

If not Its Universe

The next clear night, look up and gaze at the stars. What do you see? A swarm of random points of light? Or can you see the sky as the Anishinaabe do: a universe of stories.

The night sky “holds the cultural psyche and worldview of a people,” says Sandra Laronde. “It contains our stories. We are imprinted up there.” Laronde (Teme-Augama Anishinaabe) is the founder of Red Sky Performance, a Toronto-based company that is bridging the Western and Indigenous worlds through contemporary dance. Its new show, Trace, will debut at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Becket, Massachusetts, from August 7 to 11, a venue at the forefront of the U.S. dance world.

Red Sky’s appearance at Jacob’s Pillow, a renowned dance center, in a sense brings contemporary dance full circle to its Indigenous roots. Jacob’s Pillow founder Ted Shawn, one of the seminal figures of contemporary dance, drew inspiration from traditional Native dance. Since 1933, the Pillow has been “deeply intersected with Indigenous peoples and traditions,” says its director Pamela Tatge.

Tatge wanted to emphasize the Pillow’s Indigenous connections, both in its programming history and its location, so during the run of Trace, it is offering a weeklong program, The Land on Which We Dance, which will honor Indigenous peoples of the region. Curated by Laronde and in association with Hawaiian dancer Christopher K. Morgan and Nipmuc storyteller Larry Spotted Crow Mann, the event will feature talks, a free performance by Morgan and other Indigenous dancers and a procession. After the show will be stories, songs, and a bonfire. “I look forward to this celebration acknowledging the first inhabitants of our land,” says Tatge.

Red Sky’s Global Reach

A director, producer and choreographer, Laronde has devoted nearly two decades to creating and producing original, contemporary Indigenous performances as well as developing the next generation of Indigenous artists. She has drawn inspiration from Native peoples spanning the globe, from Mexico to Mongolia as well as from her own Anishinaabe community.

Laronde recounted her journey to promoting Indigenous dance during an advance visit to the rustic campus of Jacob’s Pillow on a hilltop in the Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts. She was there to connect with the tribes that call this place their homeland.

Laronde’s own roots lie with the Teme-Augama Anishinaabe (People of the Deep Water) in Temagami in northern Ontario. Growing up in Temagami, Laronde was on every sports team and starred in track and field. Her love of athleticism is apparent in Red Sky’s athletic performances. She says, “I experienced the incredible natural world of islands, trees, water and the Canadian Shield [the Laurentian Plateau]—the home of my parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents. It remains the source of inspiration for my performances and storytelling.”

When Laronde attended the University of Toronto, she began to study dance, and she pursued it more intensively at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in Alberta. In 2000, she started Red Sky Performance, taking the name from two words in her own sacred name. Its first performance was a multidisciplinary piece with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra at the Roy Thomson Hall. A shorter version of the show began touring in 2003 across Canada, the United States, Australia, China, Iceland, and Switzerland.

As the number of Red Sky productions grew, so did Laronde’s role at the Banff Centre. From 2008 to 2017, she served as director of its Indigenous Arts department, which experienced substantial growth in dance, storytelling, theater, music, new media film, and writing.

From Red Sky’s beginnings, Laronde reached out to create dance with other Indigenous cultures around the world, often through a shared relation with the natural world. A 2003 production, Dancing Americas, used the metaphor of the monarch butterfly migration from Canada to Mexico to explore the ancient trade routes of the First Peoples.

A different animal carried Red Sky to the world stage. In 2008, the Banff Centre and the Luminato Festival commissioned Tono, a work inspired by the horse cultures of the North American Plains and Mongolia. Laronde travelled to Inner Mongolia in China and independent Outer Mongolia to recruit dancers and singers for her production. “We didn’t speak each other’s language, but we communicated physically,” she said. The percussive stamping in Tono evoked the stampeding horses familiar to both cultures. It was performed at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the 2010 Vancouver Cultural Olympiad and again at the Shanghai International Arts Festival in 2014, with many stops in between, in Asia and Canada.

The horse also stars in a smaller production called Mistatim, which is about the taming of a wild horse of that name. A combination of dance and dialogue directed toward children, the show has a message of reconciliation—between Indigenous and non-Indigenous, girl and boy, horse and human, reservation and ranch, and adult and youth. With a three-person cast and designed to go into any community, it has performed more than 400 shows.

Since then, the pace of the productions has only increased. In the past two years, Red Sky has presented three world premieres: Backbone, a reference to the mountain ranges in the Americas that form the spine of the Earth; Adizokan, a cross-genre blend of dance, video and music presented with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra; and Miigis, an exploration of an Anishinaabe fire prophecy. Red Sky often has two productions on the road at once, in the style of another Canadian export, Cirque du Soleil, and gave more than 263 performances last year.

Red Sky has been broadening worldviews not only through its dance but through its REDTalk series. Since 2011, Red Sky has hosted these audience discussions with a wide range of artists, scientists, and other experts eight times a year in various Canadian locations, including Toronto, Sudbury, Temagami, and the Bear Island Reserve in Ontario. In May, Red Sky hosted a REDTalk discussion called Stars and Sky Stories: Indigenous Cosmology and Western Astronomy with Indigenous astronomers, astrophysicists, and a NASA astrobiologist.

Trace’s Trial

Miigis is what first brought Red Sky to the Berkshires. A Jacob’s Pillow producer saw an excerpt of the performance at the Fall for Dance North Festival in Toronto and booked it for the 2017 season of the Pillow’s Inside/Out series, free performances on an open-air stage preceding each night’s features. The dramatic show about one of the Anishinaabe prophecies wove them together with contemporary touches such as break dancing. The performance excerpt so impressed Pillow Director Pamela Tatge that she jumped at Laronde’s suggestion for another production designed for the venue’s Doris Duke Theatre. The result was the U.S. premiere of Trace.

Trace is many things to Laronde. “The idea of Trace came from the notion that all things are traceable and that what we leave behind as humans, as a culture, as a nation, and as an individual is our legacy,” she says. “Any kind of visible marks we leave behind can be seen as trace—a footprint as a culture or a scar.”

“Any kind of visible marks we leave behind can be seen as trace—a footprint as a culture or a scar.”

Sandra Laronde

Red Sky Performance Founder & Artistic Director

And all traces, she realized, have origins. “What is our origin as Indigenous peoples and more specifically, what is our origin as Anishinaabe? The search for origin took me right back to the stars and to the beginning of time,” says Laronde. “It’s exciting to think that we originated from somewhere in the core of a star a very long time ago.”

“The Western world looks at its inception as the Big Bang. For Anishinaabeg, Sky Woman begat life for humans. For example, says Laronde, “Pleiades is called the Seven Sisters and that’s where Sky Woman fell through—Pleiades—and came down to Earth through what they call a black hole.”

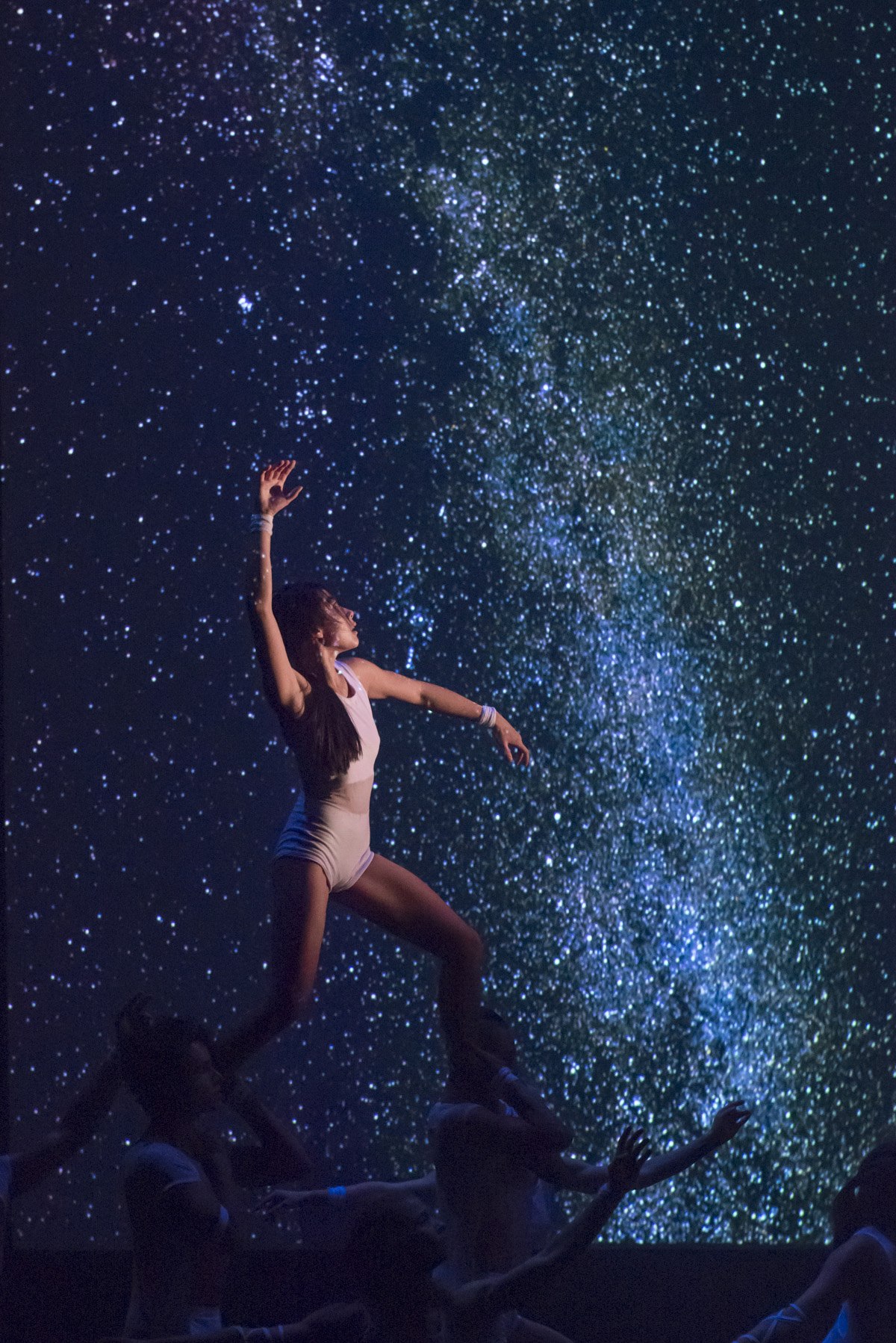

In Trace, a black hole—which the Anishinaabeg call “Bugonagiizhig”—appears, making way for a dancer’s descent to Earth from the Sky World. “The dancer looks like she’s actually walking across the sky toward the source to commune with the Milky Way,” says Laronde. The Anishinaabeg call the Milky Way “Jiibay Kona,” which is seen as a terrestrial roadway for the dead and leads back to Ishpiming, the Spirit World.

Digital interpretations of the night sky and the land saturate the screen behind six dancers on stage. Indigenous and non-Indigenous, the dancers are Eddie Elliott (Maori), Cameron Fraser-Monroe (Tla’amin), Miyeko Ferguson, Lindsay Harpham, Julie Pham, and Jera Wolfe (Métis), who also choreographed. Off to the side on stage, three musicians harmoniously interpret the connections people have with the natural world while a black hole, a digitized buffalo, constellations, trees, and other images appear on the screen. Dancers sometimes interact with the images. Marcella Grimaux created the digital media.

The original score was composed by Eliot Britton (Métis) in collaboration with Rick Sacks, Bryant Didier, and Ora Barlow-Tukaki (Maori). Live sounds were recorded by Sacks and programmed into a MalletKat, an electronic marimba. Didier plays cello, electric and bass guitar. Barlow-Tukaki sings live vocals and performs with Indigenous instrumentation such as flutes, shells, and cajóns. Recorded vocals by Marie Gaudet (Anishinaabe) and Inuit throat singer and beatboxer Nelson Tagoona infuse the dance with melodic and rhythmic phrases.

Laronde suggested that the screen behind the dancers show a 1921 letter that Canada’s Department of Indian Affairs Deputy Superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott wrote to suppress Indigenous dancing. The letter implemented the Indian Act of 1876, which banned traditional practices for Indigenous peoples in Canada. The letter stays intact for a short interval, and then the words start to crumble. They fall away off the page and form a constellation. “It hits home to people who see the letter and those racist words crumble in front of them,” says Laronde. “Without saying anything, a great deal is said.”

“Without saying anything, a great deal is said.”

Sandra Laronde

Red Sky Performance Founder & Artistic Director

Such political statements are mixed into Trace because “those kinds of letters are traces of the past but also traces of the present in terms of how people perceive and think about us as Indigenous people. We know that their thinking, unfortunately, is still alive and well to a large extent,” says Laronde.

Expanding Worldviews

Red Sky strives to change how people perceive Indigenous artistry and people through its performances. Laronde says she hopes those who see them will experience a newfound sense of appreciation for Anishinaabe culture and perhaps even learn to view the world and the universe as her people do.

The Anishinaabe have “a very multiverse perspective of the creation of Earth or of the universe,” Laronde says. “’Uni’ means ‘one’ and ‘verse’ means ‘song,’ so it’s one song. However, whose song is that? Why is there one song?”

“Our stories are not just about people or a human-centric perspective of the world,” she says. “There’s different kinds of worlds that coexist simultaneously that we walk in every day of our lives. Yes, the physical world, yes, the Earth world, but we’re connected up to the spiritual world, an underworld, and a dream world. All of these worlds exist simultaneously. I love the layered worlds and multiexperiences since it’s more reflective of our everyday experience.”

She hopes her audiences “see a more-than-human world and that the human-centric way of looking at things and perceiving the universe is so restrictive and so limiting,” she says. “Why have such a limited perception when you can widen your lens and be much more embracing of all sentient and nonsentient beings? Humans are only just one part of the profound beauty.”

The premiere of Trace

Witness the U.S. premiere of this highly kinetic contemporary dance work inspired by Anishinaabe sky and star stories, August 7-11.

The Land on Which We Dance

Join us for a week-long celebration with events illuminating an exchange of song, dance, and storytelling, including a performance by Red Sky Performance.